Download “Regulation of social media in Russia” here

As of January 2021, Russian officials estimated that there were 99 million social media users in Russia, in other words, 67.8 % of the total population. Given that social media have become one of the main forums for critical public debate in Russia, it's important to examine how the government has responded with legislation in order to counteract “imposed patterns of behaviour” (according to Putin's Presidential Decree of 2017). The European Audiovisual Observatory's latest publication: Regulation of social media in Russia proposes to do just that.

Author, Andrei Richter, Professor Researcher of the School of Philosophy at the Comenius University, Bratislava, kicks off the first chapter with essential background reading on the Russian Development Strategy of the Information Society, introduced in May 2017. Although the document briefly mentions social media platforms, its main emphasis is clearly “traditional Russian spiritual and moral values” in terms of information and communication technologies. More specific social-media related regulation would be introduced later on, as this report details, most provisions being included in the Federal Statute “On Information, Information Technologies and on the Protection of Information”, often known as the IT Law.

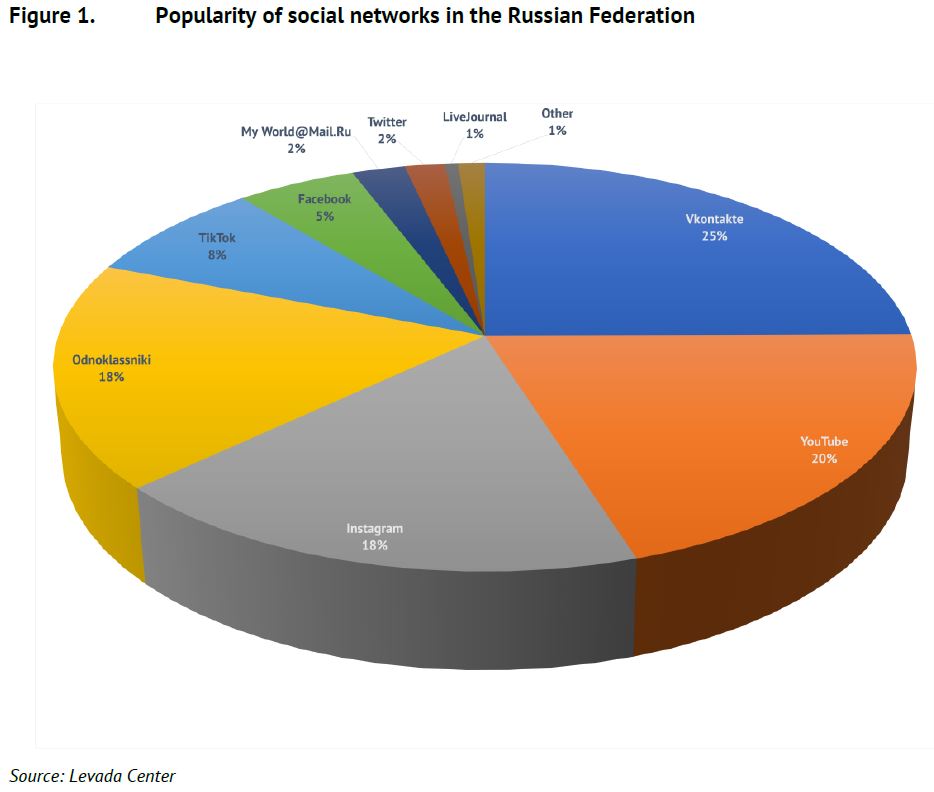

The second chapter examines the access to and penetration of social networks in Russia. The popularity trends show a steady increase of the share of Vkontakte, YouTube and Instagram, a big jump for TikTok at the expense of Odnoklassniki, and a stagnation for Facebook. Three Russian social networks from the top 10 list – Vkontakte, Odnoklassniki and My [email protected] – belong completely to one company, Mail.ru Group Limited, registered in Limassol, Cyprus.

This chapter also explores restrictions on the use of social media by certain actors. Civil servants, including those working for the Russian court system, must provide their employer with details of their social media accounts on the understanding that these may be examined. In 2019 even broader restrictions were introduced for military servicemen and civilians on army reserve duty, prohibited from posting various types of information related to military matters.

The third chapter details with the legal grounds for sanctioning social networks in Russia. All social media platforms available in Russia must store the contact data of Russian users on servers geographically located in Russia. LinkedIn refused to comply with this ruling and was effectively blocked. Facebook and Twitter also refused to comply and in February 2021 were each fined RUB 4 million. A second rule considers all social media operating from outside Russia as 'foreign agents'. They are therefore obliged to publish on every post a very prominent text warning known as a “foreign agent media imprint". The Russian state has recently introduced measures to enable the blocking of online resources owned by entities officially designated as being involved in the violation of freedom of information rights, such as recent examples of social media platforms blocking or hindering access to Russian news services.

The fourth chapter examines how Russian legislation deals with illegal content published on social media platforms. The Russian 'IT law" includes: blacklisting and blocking mechanism for sites publishing illegal content on one hand, and further dispositions which allow the identification of the different categories of illegal information, on the other. In 2019 a further category of illegal information was added: "blatant disrespect for society, government, official state symbols, the constitution or state bodies of Russia." March 2019 saw an additional amendment to the Russian IT Law resulting in the so-called “Law on Fake News”. This new disposition is aimed at counteracting threatening or harmful information or indeed “knowingly inaccurate socially significant information”. Heavy fines accompany this legislation and indeed as of June 2021, for non-compliance with the requirement to block access to prohibited materials, Facebook/Instagram has accumulated fines totaling RUB 43 million, Twitter RUB 27.9 million, and Google/YouTube RUB 6 million, as well as an additional RUB 9.2 million for “inadequate filtering of a search engine”.

The fifth chapter dives into more recent attempts in Russia to make social media platforms more responsible via self-regulation. One of the main requirements of this latest legislation, introduced in December of last year, is that social media platforms provide a clear, named contact email to allow user complaints. The platforms must then submit a yearly report on all complaints received and follow-up made.

The sixth chapter provides an overview of current Russian case law in this field. In the seventh chapter the author moves on to the most recent development dating from July 2021: the law on “grounding foreign IT companies”. The aim here is to make sure that the big social media platforms operating from outside Russia be subject to the same operating conditions as Russian-based sites and that they comply strictly with the same domestic legislation. This is achieved by obliging all such sites to open a direct online account with state regulator Roskomnadzor and strictly follow the norms of Russian law. Controversially, this new move grants discretionary, “extraordinary powers” to Roskomnadzor and allows sanctions without a court judgment.

Rounding up, the author concludes that regulation of social media platforms operating in Russia is a very recent phenomenon, its main aim being to ensure quick compliance with federal legislation and regulations, particularly concerning illegal content. Faced with the technical and strategic difficulties of blocking sites, the Russian Federation has tended to oblige social media platforms to open up branch offices in Russia, on the one hand, and take recourse to heavy financial fines to punish noncompliance, on the other.

How does Russia regulate social media platforms? Read our latest report and find out!